Tenant-Based Rental Assistance: A Cost-Effective Strategy to Reduce Family Homelessness

Image credit: Pexels

Image credit: PexelsStable, safe, affordable housing is vital for child and family health. But, a growing number of North Carolina families are experiencing homelessness. According to the 2024 Point-in-Time (PIT) count estimate, North Carolina saw the fifth largest increase in family homelessness between 2023 and 2024. Also, the number of children using McKinney-Vento services increased by 80% between the 2020-2021 (20,325) and 2021-2022 (25,427) school years. As housing costs outpace wage growth, family homelessness will continue to rise. Permanent, deep, tenant-based rental assistance is a proven and cost-effective way to reduce family homelessness. To reduce family homelessness, North Carolina should create a state-level program to expand access to permanent, deep, tenant-based rental assistance.

Definitions

Family: a household with at least one adult over the age of 18 serving as the caretaker for at least one child under the age of 18

Literal homelessness: defined by HUD as lacking “fixed, regular, and adequate nighttime residence” and used for the Point-in-Time (PIT) count.

Point-in-Time (PIT) count: a yearly survey conducted in the US of people experiencing literal homelessness on a single night in January

McKinney-Vento Act: provides services to students who meet the definition for literal homelessness or are tentatively housed (e.g., doubled up with family, living in a hotel, or substandard housing)

“Deep”: a subsidy that covers the difference between an allowable rent amount and 30% of household income

Tenant-based: assistance that is attached to a household allowing a household to move to different units

Affordable: housing and utilities are 30% or less of gross income

Cost-burden: housing and utilities are over 30% of gross income

Children under six are the most likely to be in families experiencing homelessness

Adults in families experiencing homelessness are predominantly young, single mothers working low-wage jobs due to limited education, skills, and work experience. On average, there are two children. Children under the age of six make up the majority of children experiencing homelessness. Consistent with other indicators of systemic economic and social issues, Black and Hispanic families are over-represented. Current counts likely underestimate the scope of the problem because families are more likely to be tentatively housed or have children who are too young to use Mckinney-Vento services.

Consistent evidence shows that homelessness can worsen outcomes for children

For children, experiencing homelessness can have long-term negative effects. Both exposure to homelessness before and after birth are associated with worse health and developmental outcomes. Homelessness is also associated with poorer development outcomes across multiple domains during early childhood and an increased risk for mental health issues in elementary school children. Timing and duration matter. Younger children and children exposed to homelessness for six months or longer had the worst health outcomes. For example, infants that experienced an emergency shelter stay had poorer health outcomes and higher healthcare costs compared to children that did not stay in a shelter, with some differences persisting for years.

Hard-working parents are struggling to afford housing in North Carolina

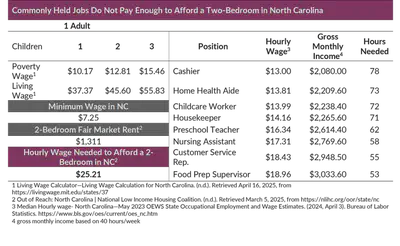

Most experts agree that family homelessness is the result of low wages combined with limited affordable housing. A 2017 study found that area level median rent was the most consistent predictor of family homelessness. In North Carolina, the 2024 fair market rent for a two bedroom was $1,311 per month. According to the National Low Income Housing Coalition, the hourly wage needed to afford a 2-bedroom in 2024 was $25.21 per hour. But the hourly wage for many jobs is not enough for a single parent working full-time to afford a 2-bedroom. There is also a significant gap in the availability of affordable units for families with low-incomes. For every 100 households at 50% AMI ($1,955 per month) or less, there are only 66 units available. Low wages combined with this gap increase the number of cost-burdened families and make it difficult for parents to find safe, stable, affordable housing.

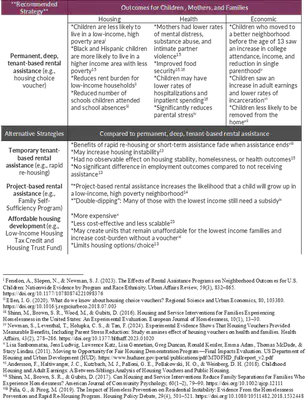

Many homelessness and housing affordability strategies do NOT reduce family homelessness

Increase supply of affordable housing: The Housing Trust Fund (HTF) and Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) are common paths used to increase housing supply, especially of project-based units. However, due to high housing costs and shrinking profit margins, units often remain unaffordable for low-income families.

Project-based rental assistance (PBRA): PBRA is attached to a development and available to a family living in one of the units. The development is likely owned by the local housing authority or built through HTF or LIHTC. Unlike TBRA, families do not have the option to take assistance with them limiting mobility and choice.

Tenant-based rental assistance (TBRA): TBRA is provided to a household as a voucher. Families with assistance can use it to make a project-based unit more affordable or can rent a unit in the private rental market. TBRA can be shallow—often a flat rate—or deep—households contribute 30% of their income toward rent. The duration of assistance may be temporary (e.g., rapid re-housing) or permanent (e.g., housing choice voucher).

In North Carolina, significant investments have been made to increase the supply of affordable housing and/or provide temporary rental assistance, in some cases with supportive services intended to address social and economic challenges. While these strategies are an important part of a comprehensive plan to address the homelessness crisis, they do not reduce family homelessness.

Policy Recommendation:

North Carolina should create a state-level program to expand access to permanent, deep, tenant-based rental assistance to reduce family homelessness and improve housing, health, and economic mobility outcomes for children, parents and families

The one strategy that has been found to improve housing quality and stability, mental and physical health, and healthcare access is TBRA. Specifically, permanent, deep, tenant-based rental assistance has the strongest evidence for reducing and preventing family homelessness, making it the most cost-effective strategy.

Despite strong evidence for permanent, deep, tenant-based rental assistance, concerns remain

Concerns over cost, effects on employment, and potential impact on rental prices have served as barriers to expanding permanent, deep tenant-based rental assistance (PDTBRA) at the federal- and state-level.

Employment: An evaluation of a HUD-funded PBRA program that included supportive services found that participation in the program did NOT affect employment. An evaluation of a second HUD funded project found that there was a small decrease in employment and earnings, but the difference was negligible.

Rental prices: A study investigating the impact of vouchers/subsidies on rental prices found that there was NO impact on rental prices.

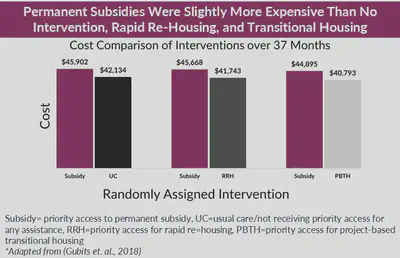

Cost: PDTBRA costs less than building new affordable units. According to a rigorous study conducted over three years, PDTBRA costs $3,768 more than doing nothing, $3,925 more than rapid re-housing, and $4,102 more than PBRA. Although alternatives to PDTBRA may cost less, these alternatives do not reduce family homelessness or improve other outcomes.

North Carolina can expand access to permanent, deep, tenant-based rental assistance through:

Direct rental assistance to families: Expanding access to rental assistance for families could be accomplished through existing programs such as the Housing Trust Fund or creating a state-level voucher program. States like Iowa, Massachusetts, and Connecticut have created state-level programs.

Owner-claimed tax credits: The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities and UC Berkeley’s Terner Center for Housing Innovation have proposed creating a renter’s tax credit program that would allow an owner who agrees to reduce rent to 30% of a family’s income to claim a quarterly tax credit.

Design considerations:

Partnering: Landlord willingness to accept a voucher is critical for success. A state-level program should focus on creating partnerships with landlords and providing rental search support for families.

Prioritizing: Timing and duration matter for children. Current evidence suggests that targeting families with children under the age of 13 would maximize benefits.

Maximizing: Moving to areas with better opportunities improves long-term outcomes. A state-level program should focus on supporting a family’s move to a lower-poverty, higher-income neighborhood.

Conclusion

Homelessness should be “rare, brief, and non-recurring”. For too many families in North Carolina, that is not the case. A comprehensive family homelessness reduction approach must address the gap between income and housing costs for hard-working families with low-income. Permanent, deep, tenant-based rental assistance is a commonsense solution for addressing this gap, reducing family homelessness, and improving housing, health, and self-sufficiency outcomes for children and families. Expanding access to permanent, deep, tenant-based rental assistance is cost-effective and would maximize return on investment. Family homelessness can be reduced in North Carolina by using resources more efficiently and investing in a state-level permanent, deep, tenant-based rental assistance program.

References (view document for specifics):

[1] Sousa, T. de, & Henry, M. (2024). The 2024 Annual Homelessness Assessment Report (AHAR) to Congress Part 1: Point-In-Time Estimates of Homelessness, December 2024. US Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). https://www.huduser.gov/portal/datasets/ahar/2024-ahar-part-1-pit-estimates-of-homelessness-in-the-us.html

[1] North Carolina Profile. (2023). National Center for Homeless Education (NCHE). https://profiles.nche.seiservices.com/StateProfile.aspx?StateID=33

[1] Haskett, M. E., & Armstrong, J. M. (2019). The experience of family homelessness. In B. H. Fiese, M. Celano, K. Deater-Deckard, E. N. Jouriles, & M. A. Whisman (Eds.), APA handbook of contemporary family psychology: Applications and broad impact of family psychology (Vol. 2). (pp. 523–538). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/0000100-032

[1] Sandel, M., Sheward, R., & Sturtevant, L. (2015). The Timing and Duration Effects of Homelessness on Children’s Health. https://childrenshealthwatch.org/wp-content/uploads/Compounding-Stress_2015.pdf

[1] Haskett, M. E., Armstrong, J. M., & Tisdale, J. (2016). Developmental Status and Social–Emotional Functioning of Young Children Experiencing Homelessness. Early Childhood Education Journal, 44(2), 119–125. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-015-0691-8

[1] Rybski, D., & Israel, H. (2019). Social Skills and Sensory Processing in Preschool Children Who are Homeless or Poor Housed. Journal of Occupational Therapy, Schools, & Early Intervention, 12(2), 170–181. https://doi.org/10.1080/19411243.2018.1523768

[1] Bassuk, E. L., Richard, M. K., & Tsertsvadze, A. (2015). The Prevalence of Mental Illness in Homeless Children: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 54(2), 86-96.e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2014.11.008

[1] Clark, R. E., Weinreb, L., Flahive, J. M., & Seifert, R. W. (2019). Infants Exposed to Homelessness: Health, Health Care Use, And Health Spending from Birth to Age Six. Health Affairs, 38(5), 721–728. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2019.00090

[1] Richard, M. K., & Shinn, M. (2024). Preventing and ending family homelessness. In G. Johnson, D. Culhane, S. Fitzpatrick, S. Metraux, & E. O’Sullivan (Eds.), Research Handbook on Homelessness (pp. 374–387). Edward Elgar Publishing. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781800883413.00040

[1] Hanratty, M. (2017). Do Local Economic Conditions Affect Homelessness? Impact of Area Housing Market Factors, Unemployment, and Poverty on Community Homeless Rates. Housing Policy Debate, 27(4), 640–655. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511482.2017.1282885

[1] Watkins-Cruz, S., & Patterson, A. (2024). Affordable Housing is Out of Reach in North Carolina for Low-Wage Workers. North Carolina Housing Coalition. https://nchousing.org/affordable-housing-is-out-of-reach-in-north-carolina-for-low-wage-workers-2/

[1] Gap Report: North Carolina | National Low Income Housing Coalition. (2023). National Low Income Housing Coalition. https://nlihc.org/gap/state/nc

[1] Byrne, T., Huang ,Minda, Nelson ,Richard E., & and Tsai, J. (2023). Rapid rehousing for persons experiencing homelessness: A systematic review of the evidence. Housing Studies, 38(4), 615–641. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2021.1900547

[1] Freedman, S., Verma, N., & Vermette, J. (2023). Final Report on Program Effects and Lessons from the Family Self-Sufficiency Program Evaluation. US Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) Office of Policy Development and Research.

[1] Finnie, R. K. C., Peng, Y., Hahn, R. A., Schwartz, A., Emmons, K., Montgomery, A. E., Muntaner, C., Garrison, V. H., Truman, B. I., Johnson, R. L., Fullilove, M. T., Cobb, J., Williams, S. P., Jones, C., Bravo, P., Buchanan, S., & Force, T. C. P. S. T. (2022). Tenant-Based Housing Voucher Programs: A Community Guide Systematic Review. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice, 28(6), E795. https://doi.org/10.1097/PHH.0000000000001588

[1] Gubits, D., Shinn, M., Wood, M., Brown, S. R., Dastrup, S. R., & Bell, S. H. (2018). What Interventions Work Best for Families Who Experience Homelessness? Impact Estimates from the Family Options Study. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 37(4), 835–866. https://doi.org/10.1002/pam.22071

[1] Fenelon, A., Slopen, N., & Newman, S. J. (2023). The Effects of Rental Assistance Programs on Neighborhood Outcomes for U.S. Children: Nationwide Evidence by Program and Race/Ethnicity. Urban Affairs Review, 59(3), 832–865. https://doi.org/10.1177/10780874221098376

[1] Ellen, I. G. (2020). What do we know about housing choice vouchers? Regional Science and Urban Economics, 80, 103380. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.regsciurbeco.2018.07.003

[1] Shinn, M., Brown, S. R., Wood, M., & Gubits, D. (2016). Housing and Service Interventions for Families Experiencing Homelessness in the United States: An Experimental Evaluation. European Journal of Homelessness, 10(1), 13–30.

[1] Newman, S., Leventhal, T., Holupka, C. S., & Tan, F. (2024). Experimental Evidence Shows That Housing Vouchers Provided Measurable Benefits, Including Parent Stress Reduction: Study examines effect of housing vouchers on health and families. Health Affairs, 43(2), 278–286. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2023.01020

[1] Lisa Sanbonmatsu, Jens Ludwig, Lawrence Katz, Lisa Gennetian, Greg Duncan, Ronald Kessler, Emma Adam, Thomas McDade, & Stacy Lindau. (2011). Moving to Opportunity for Fair Housing Demonstration Program—Final Impacts Evaluation. US Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). https://www.huduser.gov/portal/publications/pdf/MTOFHD_fullreport_v2.pdf

[1] Andersson, F., Haltiwanger, J. C., Kutzbach, M. J., Palloni, G. E., Pollakowski, H. O., & Weinberg, D. H. (2018). Childhood Housing and Adult Earnings: A Between-Siblings Analysis of Housing Vouchers and Public Housing.

[1] Shinn, M., Brown, S. R., & Gubits, D. (2017). Can Housing and Service Interventions Reduce Family Separations for Families Who Experience Homelessness? American Journal of Community Psychology, 60(1–2), 79–90. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajcp.12111

[1] Piña, G., & Pirog, M. (2019). The Impact of Homeless Prevention on Residential Instability: Evidence from the Homelessness Prevention and Rapid Re-Housing Program. Housing Policy Debate, 29(4), 501–521. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511482.2018.1532448

[1] Shinn, M., & Khadduri, J. (2020). Changing Societal Conditions that Generate Homelessness. In In the Midst of Plenty: Homelessness and What to Do About It (1st ed.). Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119104780

[1] Deng, L. (2005). The cost‐effectiveness of the low‐income housing tax credit relative to vouchers: Evidence from six metropolitan areas. Housing Policy Debate, 16(3–4), 469–511. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511482.2005.9521553

[1] Fischer, W., Acosta, S., & Gartland, E. (2021). More Housing Vouchers: Most Important Step to Help More People Afford Stable Homes.

[1] Eriksen, M. D., & Ross, A. (2015). Housing Vouchers and the Price of Rental Housing. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 7(3), 154–176. https://doi.org/10.1257/pol.20130064

[1] Gubits, D., Shinn, M., Wood, M., Bell, S., Dastrup, S., Solari, C. D., Brown, S. R., McInnis, D., McCall, T., & Kattel, U. (2016). Family Options Study: 3-Year Impacts of Housing and Services Interventions for Homeless Families. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3055295

[1] Fischer, W. (2019). Rental Housing Programs for the Lowest- Income Households: Renters’ Tax Credit. National Low-Income Housing Coalition. https://nlihc.org/sites/default/files/AG-2021/04-19_Rental-Housing-Programs-Renters-Tax-Credit.pdf

[1] Galante, C., Reid, C., & Decker, N. (2016). The FAIR Tax Credit: A Proposal for a Federal Assistance in Rental Credit to Support Low-Income Renters. Terner Center for Housing Innovation. https://ternercenter.berkeley.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/FAIR_Credit.pdf

[1] Kimberlin, S., & Kneebone, E. (2024). Options for Addressing Rent Burdens Through the Tax Code: Considerations for Designing a Renter’s Tax Credit. UC Berkeley Terner Center for Housing Innovation. https://ternercenter.berkeley.edu/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/Terner_Options-for-Addressing-Rent-Burdens-Through-the-Tax-Code.pdf